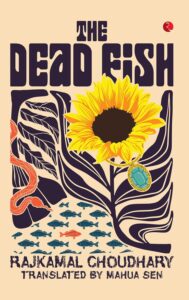

Mahua Sen speaks to EKL Review on her translation of Rajkamal Choudhary’s Hindi novel (Machhli Mari Hui) into English, The Dead Fish (Rupa Publications 2025)

- What is this book about and how did you come across to translating it?

The Dead Fish (Machhli Mari Hui) is not merely a book you simply read, it’s an experience you reckon with. Rajkamal Choudhary had the nerve to engage with as incendiary subject as same-sex desire at a time when even acknowledging its existence was considered blasphemous. But this novella is not just a representation of queer desires, it’s a work that simultaneously champions the existence and presence of queer people while condemning hypocritical societal behaviours. It’s an exploration of the human psyche, fractured identities, stifled desires, the brutal anatomy of gender politics, and the in-betweenness of being. It sets you on fire and ice, stillness and whirl, all at once.

I stumbled upon this book during my undergrad, and only in the extended lockdown did it come back to me during a conversational deep dive into Hindi Sahitya with a friend,which led me back to Rajkamal Choudhary. This time, it meant something starkly different. I remembered his origins from Mahisi (Saharsa) in North Bihar, which connected to my father working in that district years ago as the Chief Medical Officer. This coincidental but factual connection did not feel like a mere fact but more a ‘kismet connection.’ I took it upon myself to revisit. Slowly. This time, however, it was the narrative that had me gobsmacked. It was not the story that trapped me, but the cadence in which it was relayed, the metronome of power and pain, a connection from somewhere within my navel, that felt umbilical, anankastic and utterly unavoidable. And then came that ‘never-before-felt’ urgency from within myself to take it beyond Hindi.

Translating Machhli Mari Hui came over time, not immediately. When faced with such an intense and pulsating prose like Rajkamal’s it was bound to be difficult to gather the courage to embark on such a task, yet eventually I took the plunge into the deep waters, which later became an extremely intimate endeavour.

- How was your translation experience?

I almost felt like diving into the waters, not knowing how to swim, just to retrieve something that was gasping for breath. That’s what translating Machhli Mari Hui felt like. Rajkamal Choudhary doesn’t hand you a neat narrative. He throws you into a whirlpool of broken desires, fetid socioeconomics and breathless bodies. It doesn’t follow a conventional narrative arc. There is no beginning, middle, and end. There are fragmented decrepit disconcerting narratives yet at the same time, so starkly realistic. So raw.To translate that was to walk the line between exasperation and empathy, pain and yearning.

There were nights I sat with a sentence or a word for hours, thinking,how could I carry this without mollifying the ferocity, without aestheticizing it. Because that is exactly what I’ve tried to do, I’ve not tried to sugarcoat the bitterness, or join the disjoined narratives. I’ve not tried to fill the ellipses. I’ve let the condemnatory tenses remain even if it switches back and forth, dawdling between past and present tense, because maybe this hints at chaos and confusion.

There were other times I felt held hostage by the characters, especially the women who were written about in such startling rage and rawness that they needed more than translation. They needed compassion, and in the process, I forgot that I hadn’t created them, originally. I felt like the biological mother, who not only birthed them, but took the responsibility, inhabited their world, their wounds, trying to recreate them in another tongue without betrayal, in all truthfulness. In that sense, I became the Sutradhar, the thread-holder, perhaps not the weaver, but the one who keeps the fragments from falling apart. It was a massive responsibility. Yes, I did experience the Braxton hicks contractions of birthing a child, so to say.

I had not set out to translate Machhli Mari Hui immediately. It happened over time. The intensity of Rajkamal Choudhary’s pen, the beating heart behind the writing, kept me for a long time uncertain about whether I’d be able to ever accomplish such a feat. Yet I took the leap. And it proved to be one of the most intimate experiences of my life. It was not an exercise in translation but an experience, an engagement not only with language and narrative, but with silence, with trauma, with politics of invisibility. It was asking for a lot from me and in return, it took me to the untrodden territories deep within myself that I hadn’t explored before.

- Issues of homosexuality and bestiality are difficult to handle whether in original or translation because it is not done in a regular rhetoric. How difficult it was for you?

These ideas are not themes per se, in Machhli Mari Hui, rather, they are subthemes, an undercurrent, a challenge, or a break in language itself. Instead of giving a didactic commentary on homosexuality, Rajkamal Choudhary immerses the reader in the inner turmoil of his characters’ lives, where they exist in disassociation, refusal, and desire. Additionally, the language is not simple; it is polyphonic, fragmented, and alternates between satire, stream of consciousness, and poetic form. Translating such texts wasn’t just a technical task, it demanded an emotional, empathetic, and ethical negotiation.

So yes, it was hard, yet most fulfilling. Because Machhli Mari Hui attempts no resolutions, it challenges the audience to acknowledge the harsh reality that lies underneath the pretence of culture, civilized society, and morality. It does not resolve, it reveals.As a translator, my responsibility was to retain the rawness, sans any toppings. It was to reveal the unrevealable.

- How does the metaphor of the dead fish come out in your translation and what is your expectation from a typical reader?

One of the hardest parts was staying true to the ‘decaying grandeur’ of Rajkamal Choudhary’s metaphors, like the title itself, Machhli Mari Hui. It isn’t just a dead fish. It’s a metaphor for something that once had life, now lifeless, entrapped, and discarded.How does one translate that sense of redundance and stillness into English? You can’t sanitize it. You must let it decay. Thus, in translation, I did not aim to explain, I allowed it to reverberatein the characters’ inhales and exhales, in the pauses between their breaths, in the disjointedness of narrative. The “dead” is corporeal and psychic, from culture to society. So I tried to preserve the fragmented sentences, shifts in tone, repeated language and the confused jumble.

I didn’t attempt at satisfying my readers. On the contrary, I wanted my readers to be unsettled, disquieted, perplexed. This is not a book that ends with resolution or cathartic release. This is a book that breathes life into harsh realities of an existence that many people would prefer to ignore. If someone puts this book down because she feels she has seen too much but also wants to re-see, and re-read, then I have succeeded as a translator.